Crystal Cove Alliance keeps history alive with its thriving Historic District and plans to renovate the remaining 17 North Beach cottages for public use.

By Ashley Breeding

Bud Carter, 88, stands before Crystal Cove’s Cottage #7. His mouth forms a quivering smile and tears well in his eyes as a wave of nostalgia as powerful as the ocean behind us washes over him.

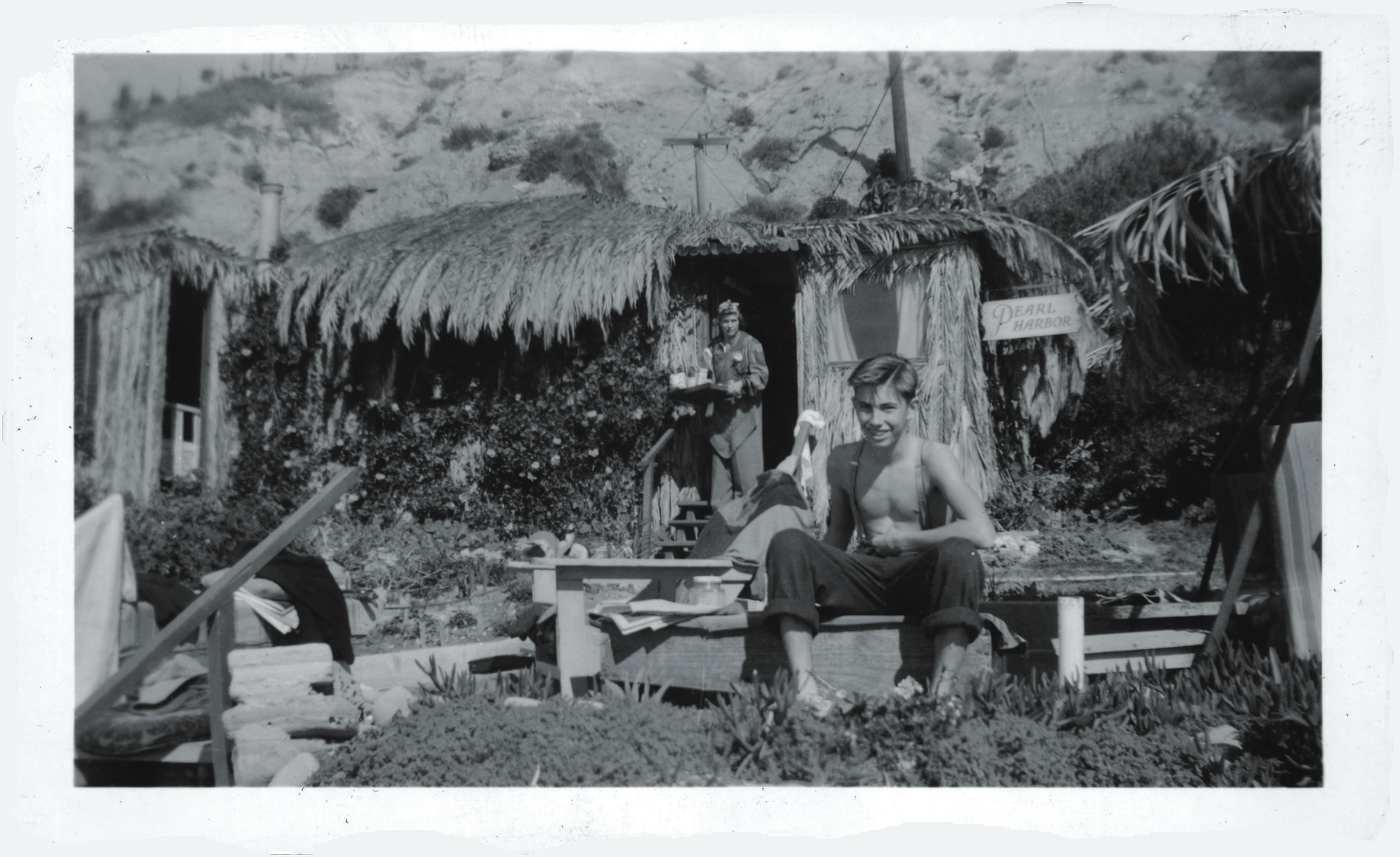

The cottage, nestled in the hillside of Crystal Cove’s Historic District, is the ramshackle remains of Bud’s family vacation home since childhood. The once palm-thatched roof is nothing but bare gravel. The wood-framed windows are weathered, chips of turquoise paint peeling from years of wind and salty air. A small, matching picnic table waits on the porch for a family to gather around for another barbecue.

“This is the first time I’ve been back in 12 years,” Bud says. “I just haven’t been able to bring myself here until now.”

Bud’s old bungalow is one of 46 at Crystal Cove, where an eclectic community of early settlers, self-proclaimed “Covites,” lived and holidayed from the 1920s until 2001, when California State Parks required everyone to move out, as their leases expired, for much-needed repairs and renovations.

Inside, the creaky hardwood floors are littered with shards of glass and blanketed with dirt. The only signs of life are native plants that have trespassed through crevices. Strangely, two white islet window curtains appear newly hung.

As Bud reminisces about summers of decades past—a seemingly simpler and sweeter time when teenagers spent their days fishing and surfing beneath the sun, and evenings listening to Benny Goodman and “cutting a rug” on the deck of The Store nearby—it’s easy to imagine the cove in its heyday. He paints a picture of a place ripe with color, both in landscape and the eccentric community that graced it.

“I couldn’t have picked a better time to live here,” he says. “I was so fortunate to have been part of such a special place that so few people got to experience.”

Early 20th Century Charm

A once-overlooked area of the Irvine Ranch (white sand beaches weren’t of much use for cattle), the cove became a popular haven for Irvine Co. workers seeking respite, plein-air painters from Laguna Beach (William Wendt is the first known to paint here) and silent movie-era Hollywood filmmakers scouting “island” locations.

Since James Irvine didn’t mind people using his land to camp, Crystal Cove, over time, evolved into a community all its own. Settlers from various walks of life assembled beach-side bungalows from whatever materials were available to them—lumber from a shuttered warehouse in Los Angeles, discarded sinks from the Hotel del Coronado, window panels from abandoned railway cars. A wooden schooner that washed ashore in a violent storm in 1927 became an abundant resource for building materials.

One brick-colored cottage at the district’s northern tip once stood in San Marino, recalls Laura Davick, founder and director of public affairs for Crystal Cove Alliance (CCA), a nonprofit partner of California State Parks dedicated to conservation, restoration and education.

“The family [dismantled] and moved the home to Crystal Cove, where they put it back together by hand,” she explains. “One of the residents told me she remembers having to bang all of the square nails out of the boards, one by one, when she was just a little girl.”

Crystal Cove Historic District was listed on the National Register of Historic Places through the efforts of former Covites. When the land was purchased by California State Parks from The Irvine Co. in 1979, it was deemed to be the last intact example of early vernacular architecture along the Southern California coast, Laura says.

Having grown up here, it is personally important to Laura—imperative, even—that this “unique microcosm of California history” be protected and restored; in 1999, she founded CCA to halt a planned luxury resort and rescue the historic site. Plans to restore the cove soon followed and, together, CCA and California State Parks acquired more than $22 million––via grants, generous donations and tireless fundraising—to begin renovations on the historic cottages.

The plan called for three phases: The first two, completed in 2006 and 2011, respectively, included restoration of 29 of the historic cottages—which now serve as overnight rentals, educational venues and dining establishments—as well as new infrastructure and additional facilities for guests and visitors.

What makes the Crystal Cove renovations particularly special is that these structures were all restored to look exactly as they did in the early 20th century. In many instances, original materials were salvaged. From the landscape to window treatments to paint colors, the modern-day structures you’ll visit today reflect the very images you’ve seen in old landscape paintings by artists such as Wendt, Edgar Payne and Roger Kuntz. To stay in a cottage here is truly like stepping back in time—nowhere else in Southern California does such an experience exist. These restorations earned Crystal Cove State Park a prestigious Governor’s Historic Preservation Award in 2007.

“The restoration is all about providing a unique opportunity for the public,” says Dan Gee, a CCA board member who serves as its representative on the Phase III restoration project. “Everyone should have this kind of beach experience at an affordable cost.

“It’s incredible how many people, residents, in particular, … regularly drive the stretch of Coast Highway right above the cove and don’t even know what’s down here. We hope that by restoring it, more people will discover and get to enjoy it.”

The Final Phase

The south end of the historic district is alive and blossoming once again, now welcoming more than 800,000 visitors annually who come to rent out the renovated cottages, dine at the Shake Shack, The Beachcomber Cafe and Bootlegger Bar, and explore Crystal Cove’s 3-plus miles of pristine coastline and underwater park.

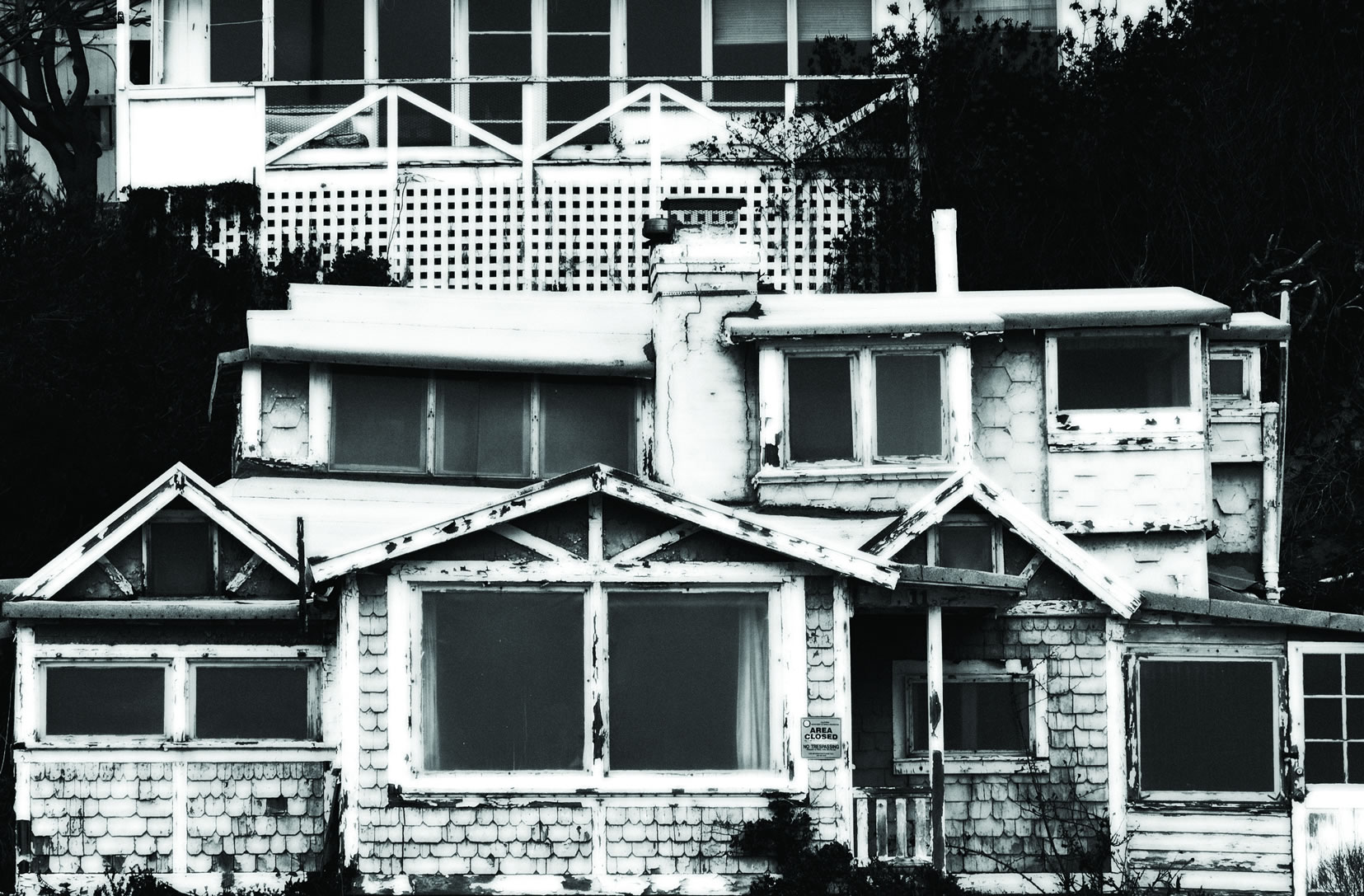

The northern landscape, however—still vibrant with overgrown bougainvillea and desert flowers among the eucalyptus trees and ice plant—juxtaposes a cluster of tired old houses dotting the bluff, all barely hanging together by a few nails. An earth slide at one side has forced a cottage in its path to lean outward. If it isn’t soon restored, its precious parts may be lost forever.

A devastated boardwalk, which at one time stretched the entire 700-foot length of the homes, is now split and scattered.

It is now CCA’s hope that the organization can raise the funds necessary to repair this last region of the historic park and offer 17 more overnight rental cottages to guests.

The project (Phase III), now under evaluation, is estimated to cost $20 million. Seven million dollars will cover the infrastructure—reconstruction of the historic boardwalk, retaining walls, electricity and plumbing—which is the initial step of the project. Engineers are also studying how predicted sea level rise will affect the area and assessing how to move forward with the restoration.

During a time when California State Park budgets are threatened, CCA is compensating for the deficit at Crystal Cove with its own concession revenue—12 percent is reserved for maintenance that would normally be paid for by the state, as well as future restorations. For this reason, CCA does not have the funds to complete the restoration and is relying heavily on the community to see the project to fruition.

“If we were to have all of the funding today, this would be a five-year project,” Laura estimates. “But without the community’s support, we won’t be able to make it happen.”

The project recently has secured $5 million in mitigation funds from the California Coastal Commission, a commitment supported by former Executive Director Peter Douglas, who frequented the cove and was profoundly inspired by the restoration efforts.

“This initial funding enables CCA and California State Parks to begin work on early planning, engineering and permitting,” Laura says. “This is an incredible milestone for CCA and culminates a six-year-long effort.”

“Crystal Cove is one of those rare examples where people can enjoy a million-dollar beach experience on a working-class budget,” says Mary Shallenberger, California Coastal Commission chairwoman. “This project is good for public access and preserves an important piece of California history for families and future generations. There is no place like the cove—it’s a unique gem.”

Director of California State Parks, retired Maj. Gen. Anthony Jackson, echoes Mary’s sentiments: “Crystal Cove is an example of that period in our history most associated with California’s beach culture,” he says. “These significant cultural landscapes tell the stories of the generations of Californians who preceded us—the people who helped mold a unique California lifestyle. The restoration of the Crystal Cove historic district brings one chapter in our history to life, and that is something to be honored and preserved.”

Director of California State Parks, retired Maj. Gen. Anthony Jackson, echoes Mary’s sentiments: “Crystal Cove is an example of that period in our history most associated with California’s beach culture,” he says. “These significant cultural landscapes tell the stories of the generations of Californians who preceded us—the people who helped mold a unique California lifestyle. The restoration of the Crystal Cove historic district brings one chapter in our history to life, and that is something to be honored and preserved.”

He also believes the historic district serves as a model that should be replicated by other state parks. “It is not just a historic site; it pays its own way,” he explains. “By applying ‘adaptive reuse’ to this site, we not only preserve history, we make it self-sustaining through the rents paid for overnight stays in the historic cottages. With the help of our good partners, Crystal Cove Alliance, we have transformed this historic site into a place where visitors can experience and enjoy it as it was when it was a vibrant community decades ago.”

Peter Ueberroth, a prominent Orange County resident who has skin-dived along the cove’s shores since 1944 (“more times than almost any other citizen”), conveys the importance of the project as well as the community’s involvement.

“[This] project is important to all of Orange County,” Peter says. “It links Corona del Mar and Laguna Beach, and is among the most beautiful beaches in the state of California. The cottages and amenities are a must for both local residents and visitors alike. Once completed, it will be the best example of a public-private partnership in the state park system.”

Those who have had the privilege of living at Crystal Cove, explored its natural wonders or simply taken a barefoot stroll along its shore know what a truly special place it is. Original residents like Bud and kids exploring the beach for the first time are able to share the treasured space today, thanks to the partnership between CCA and California State Parks along with generous support from the community. With their continued work and collaboration, generations to come will have the opportunity to experience the history and culture preserved in the cove. NBM

What You Miss When You Drive By

Sweeping ocean views to one side and an idyllic canyon on the other are what most people see when cruising past Crystal Cove State Park on Pacific Coast Highway at 50 miles per hour. It’s a sight that inspires extra glances and deep breaths to take in the cool sea breeze. But what you see in a blur is a mere snapshot of the state park’s beauty. With more than 3 miles of pristine beach, 2,400 acres of protected chaparral habitat and 1,100 acres of underwater park, it’s impossible to fully comprehend the historic charm, physical beauty and ecological importance that characterize Crystal Cove from inside a passing car.

Barely visible from the highway, 46 cottages originally built from the 1920s to 1930s dot the shore; 29 are now available for rent and public use, thanks to preservation efforts spearheaded by Crystal Cove Alliance and California State Parks. The park’s diverse terrain and offshore expanse welcome campers, hikers, divers and other outdoor enthusiasts, and protected populations of flora and fauna intrigue everyone from leading scientists to Girl Scout troops.

In this series of articles, we uncover the many layers of Crystal Cove that are easily overlooked when just driving by on your daily commute, but aren’t soon dismissed when you take the time to discover the stories that make up this fascinating area.