Former California Angel Jim Abbott proves that a so-called disability can also be a blessing.

By Brett Callahan

As a little boy growing up in Flint, Mich., Jim Abbott used a doctor-prescribed hook on his missing right hand to break Coke bottles in half while pretending to be Steve Austin from “The Six Million Dollar Man.” The idea that someone labeled as “different” could be a superhero for others helped Jim cope with a birth defect that would directly shape the course of his life. The short-lived hook soon gave way to a baseball glove, and the shattered bottles to broken swings of baffled hitters, as Jim worked himself into one of the most electrifying and idolized baseball players of his era.

Kathy Abbott used to preach to Jim and his younger brother, Chad, that each level of life should be treated as a gift, and that they had a responsibility to live up to that gift. Jim’s latest venture, co-authoring his own life story, “Imperfect: An Improbable Life” with veteran sports writer Tim Brown, is his most recent attempt to honor his mother’s expectation of her sons. Sandwiched between a retelling of Jim’s perfect game that he pitched as a member of the New York Yankees on Sept. 4, 1993, the autobiography, published in 2012 by Ballantine Books, covers the many ups and downs of Jim’s journey through life on and off the mound.

“It was by far the most satisfying experience of my career because I felt like we were working on something of real value,” Tim says of writing with Jim. “In a world that’s become fixated on the weird, the loud and the unaccountable, Jim’s story had a real message with a real depth to it that could maybe help some people.”

As the Corona del Mar resident and family man turns to the next phase of his inspirational career as a motivational speaker and author, Jim continues to serve as a hero in his own right as he proves that passion overcomes perception.

Finding the Zone

The yarn packed inside of a baseball, typically just 3 inches in diameter, can reach lengths of up to one full mile. Like that yarn stretched to its limits, Jim has always known how to get the most out of his given talents since first picking up a baseball as a youth in Flint. Searching for acceptance and a place where he didn’t have to dive his right arm into his jean pocket for fear of wandering eyes, the baseball diamond quickly became Jim’s great equalizer.

“There were times where my hand was something I was confronted with and had to deal with, but on the field, on that pitcher’s mound, that was my chance to fight back and feel like everybody else,” Jim says.

As Jim’s talents developed, few actually felt the same level of success Jim would as a leader on the ball clubs of Flint Central High School, the University of Michigan and the United States 1988 Olympic team. The accolades, no-hitters and victories that rapidly accumulated, took Jim to places and people he never imagined possible.

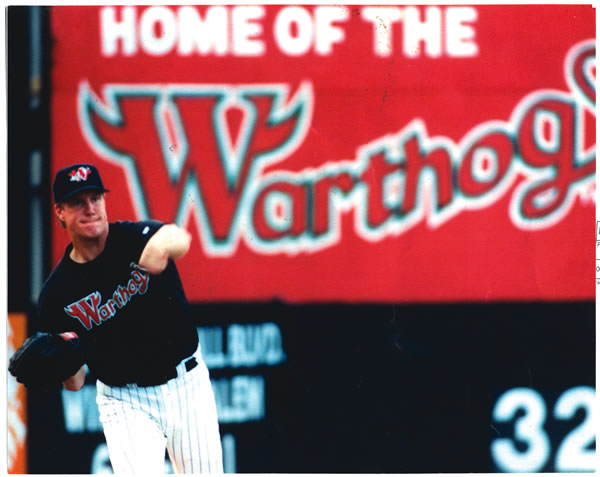

The California Angels made Jim their first round pick in the 1988 draft, and he quickly joined their starting rotation without playing a single minor-league inning. The national attention for the rookie phenom came not only because of Jim’s fastball cutter, but because of what he represented as an athlete in direct defiance of accepting the norm.

“I don’t know what I would have been had I been born like everybody else,” Jim says. “I have a feeling that I wouldn’t have been as driven or had the same type of ambition. I don’t know that I would have pushed myself in ways that I did as a kid, and so I’m thankful for it.”

Whether he initially wanted to or not, Jim unofficially became the spokesperson for differently-abled athletes everywhere. It started slowly with a few dozen fan letters from children and their parents wanting encouragement and validation, but those numbers soon grew to hundreds, and the letters turned into clubhouse visitors. Departing earlier and earlier from card games and other pregame activities with teammates, Jim consistently made time each game to meet with those who sought so desperately to see, touch and hear from him. As the visits became more consistent and personal, so too did grumblings from certain managers and teammates that the interactions took away from his focus on the game.

Over the course of Jim’s decade-long career in baseball, he would experience some drastic highs and lows, like the 18 wins he had in 1991, and the 18 losses he endured just five seasons later. The statistical variations may have temporarily raised chatter about his off-the-field obligations, but Jim never saw it as anything more than living up to the responsibility of his hand.

“This was his to celebrate, to endure, to carry, and it wasn’t a choice he made, it was his duty. And along the way it became his honor,” Tim says.

Now 45, Jim continues to pledge himself to that honor. The clubhouse may be replaced by a Boys and Girls Club hallway and the pant-leg pinstripes are on that of a designer suit instead of sliding pants, but Jim still has an audience to dominate. He takes to the podium, his replacement mound, and delivers his story to audiences ranging from corporate sales teams to the local Challenger Division of Little League, hoping the message resonates with at least a few.

“Motivational speaking tests you. There’s definitely performance anxiety,” Jim says. “It pushes you in a lot of the same ways pitching does, and it’s rewarding in a lot of the same ways. It’s all about trying to encourage people to see the possibilities in life.”

Home Base

Baseball brought Jim victory, fame, camaraderie and an opportunity to reach thousands, but perhaps most importantly, it brought him to the location where he would make a future for his family. As a rookie with the Angels, Jim turned to his teammate, Chuck Finley, when first looking for a place to settle in for his inaugural season. Chuck, who lived in an apartment in Newport Beach, took Jim in as his roommate and the Newport community took care of the rest.

“I got a taste of the beach life and being close to the water,” Jim says. “It just seemed like such a great place to live.”

While searching for a home a few years later with his wife, Dana, Jim followed his friend and mentor Kirk McCaskill to Corona del Mar to further plant their family’s roots. Except for a few stops while playing for the Yankees, White Sox and Brewers, Jim has made the Newport community home for 24 years now. In that time he’s seen a vast growth both in the community and in his own family. He and Dana spend most of their time keeping up with their teenage daughters Maddy and Ella, and their active schedules full of volleyball, water polo, soccer and school.

“You can get anything you want in Newport. You can have a quiet cul-de-sac with kids riding their bikes and shooting hoops, and have all the athletic and scholastic opportunities for your kids,” Jim says. “I think they get a chance to experience a lot of the best things that are possible in the world. There’s people that aim high here and want to do great things, and I enjoy the idea that my kids are exposed to that.”

When free time does present itself during breaks from serving as a chauffeur to Maddy and Ella, speaker, author and volunteer, Jim takes advantage of the simple pleasures of coastal living.

“I really enjoy the outdoor activities here,” he says. “I run down on the beach at Big Corona quite a bit [to] take it easy on the knees and get off the pavement. It’s just so stunningly beautiful to get down there.”

As for a post-run meal, Jim often fuels up at favorites like Bear Flag Fish Co. and Cappy’s Cafe, a spot he used to dine at for pre-game meals with Chuck. Several local institutions like The Cannery show their appreciation for the local resident by displaying autographed jerseys from his Angels days, a subtle reminder of how far he’s come since his time spent proving himself on the little league fields of Flint.

“I’m very lucky. I really like living here in Corona and have a lot of great friends and family nearby,” Jim says. “My post baseball life has been a blessing in almost every way.” NBM

For those who think the national attention for Jim Abbott came strictly because of his physical challenges, the accolades he earned along the way prove otherwise. Having won the James E. Sullivan Award for the top amateur athlete in the United States in 1987, Jim then spent the summer of 1988 pitching for the United States team during the summer Olympics. He finished his collegiate career as the Big Ten Athlete of the Year and later had his jersey retired by the University of Michigan.

Jim’s transition into the majors led him to some early success while with the California Angels from 1989 – 1992. He finished third in voting for the Cy Young Award by winning 18 games with an ERA of just 2.89 during the 1991 season, and followed that by winning the Tony Conigliaro Award in 1992, annually awarded to the player in baseball who best demonstrates courage, determination and spirit while overcoming an obstacle. His time with the New York Yankees from 1993 to 1994 included his historic no-hitter. Jim finished his career spending time back with the Angels in 1995 to 1996, the Chicago White Sox in both 1995 and 1998, and the Milwaukee Brewers in 1999. In 2007, Jim was elected to the College Baseball Hall of Fame.