Booze and Bacchanalia

The peace-and-quiet contingent seems to have won the great Balboa battle over bands, booze and bacchanalia. But it wasn’t always so, oh no! – By Jim Washbur

It may finally have been the end of an era this past May when the Newport Beach City Council passed a “Loud and Unruly Gathering” law, allowing police to levy hefty fines of up to $3,000 for unruly, drunken, loud, urinating behavior at parties in the city. The fines, which start at $500, can be given, at police discretion, not just to each individual lout, but to the party sites’ renters, landlords and practically even the utility providing the electricity. Since the law is none too exact on what the threshold for a violation is, it is expected to have a chilling effect on the city’s party scene, where people may become hesitant to risk any activity livelier than double-dipping in the fondue pot.

It may finally have been the end of an era this past May when the Newport Beach City Council passed a “Loud and Unruly Gathering” law, allowing police to levy hefty fines of up to $3,000 for unruly, drunken, loud, urinating behavior at parties in the city. The fines, which start at $500, can be given, at police discretion, not just to each individual lout, but to the party sites’ renters, landlords and practically even the utility providing the electricity. Since the law is none too exact on what the threshold for a violation is, it is expected to have a chilling effect on the city’s party scene, where people may become hesitant to risk any activity livelier than double-dipping in the fondue pot.

What has happened, Newport? There was once a time when Newport Beach was the skanky party queen of the coast; when to neighboring O.C. burgs it must have seemed like the entire town was a loud and unruly gathering. For the better part of a century, it was the place to go when you were looking to let your hair down and drink yourself into a fuzzy did-your-dock-hit-my-boat level of insouciance.

Newport’s allure as a party town stretches back at least to the 1920s. We can probably thank Henry Huntington. The tycoon had a knack for buying up cheap property in remote areas of Southern California and then making a killing after he’d made the areas not so remote by running light rail tracks to them.

That’s what he and partners did in Newport, and a Pacific Electric Red Car line followed 1905. The tracks were extended down the Balboa Peninsula the following year. Along with being a boon to the real estate market, it opened the sleepy beach town to tourism.

The Red Cars rode practically to the door of the Balboa Pavilion. Built in 1906 specifically to draw leisure-oriented folks to the then nearly unoccupied peninsula, it did its job well. The Pavilion—which still looks much as it did then—became a destination for both sport fishermen and to those fishing for the opposite sex at evening dances. In its 1930s heyday, it hosted the Benny Goodman orchestra and other big bands.

Its success was overshadowed by that of the Rendezvous Ballroom. Today, there is nothing but a historical placard top mark where the sprawling 4,000-capacity dancehall stood between Washington and Palm streets, but for decades it entirely lived up to its name, becoming ground zero for a good time in O.C.

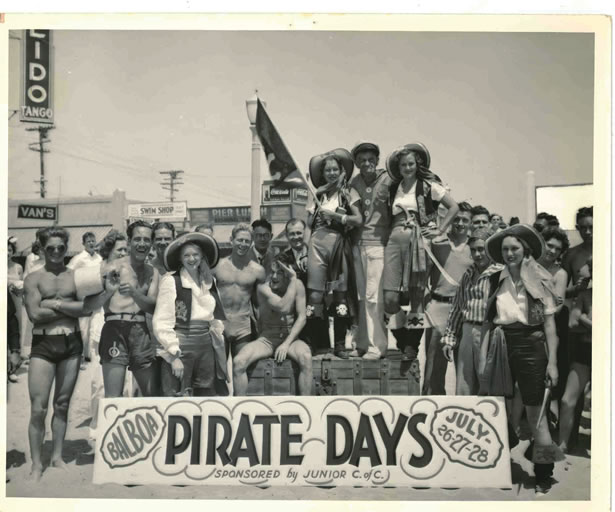

Built in 1928, the Rendezvous had a 12,000-square-foot dance floor, and had no trouble filling it. The national magazine Look dubbed the Rendezvous “the Queen of Swing,” and most of the top big bands played there, including those of Goodman, Glenn Miller, Tommy Dorsey, Artie Shaw, Harry James and Gene Krupa. In 1941, Stan Kenton began a long association with the venue (which culminated in him owning the place for a while in the 1950s). It’s not every peninsula that has its own dance: The exuberant Balboa, which is still popular with swing dancers worldwide, originated at the Rendezvous.

Howard Rumsey, who was Kenton’s bass player before becoming a legendary concert promoter, told Jazz Times magazine, “If you weren’t in Balboa during Bal Week, you weren’t living.”

He’s referring to the spring break tradition that took root in the 1930s. Most of the big band dances and other activity in Newport took place during the summer. It became a ghost town for much of the rest of the year. The exception was Easter week, when a summer’s worth of action would be jammed into one beer-laden mating dance of a week. It’s curious that Easter, which was adapted from pagan fertility rites, became the time for a revelry named Bal Week, so similar to the ancient Egyptian fertility god Baal.

College kids, high school kids and anyone else aspiring to ever get laid in their lives made the Balboa peninsula their destination. Once school was out, youths from O.C., L.A. and points beyond all converged on Balboa, via the Red Car (until it was discontinued in 1940) or in jalopies that so filled every street that emergency vehicles had trouble maneuvering through them.

Those vehicles were sometimes needed. Though Bal Week was surprisingly peaceful by modern standards, you don’t get that crush of people, alcohol and the sexes trying to impress each other without brawls, lifeguard tower topplings and would-be daredevils with broken pates to contend with.

The week was an annual madhouse, where every rental bungalow would be crammed with dozens of extra guests, while the human overflow slept on porches, in garages or carports and on the beach.

Bal Week was a mixed blessing, but a mix that worked for Newport. There weren’t that many year-round residents to be inconvenienced by the throngs, and the tax revenue from suntan oil sales alone probably more than made up for the cost to city services. What if zinc oxide wasn’t your thing? There was plenty of swankier action to be had in Newport as well. Several movies stars sojourned, lived or had boats here, including Errol Flynn, Humphrey Bogart, Ray Milland, Richard Boone and longtime resident John Wayne. It was far from Hollywood’s tattle-rag photographers, and a nice place to settle in for some serious drinking.

Overlooking the Back Bay, the Castaways Club offered a darkened Vegas lounge atmosphere perfect for secret assignations and shady deals. At Balboa Island’s White’s Pub, rooms upstairs were available for hourly rental, in case you happened to notice the place was crawling with hookers. For a time, a well-heeled whorehouse also operated upstairs at CdM’s classy Hurley Bell, where the Five Crowns now resides.

For those with simpler tastes, the peninsula’s Bamboo Room offered jazz combos, while the Beach Roamer had an indoor fire pit to warm the nights. The Arches, then and now, was a fine watering hole and restaurant.

As tastes changed, a new scene grew up in Newport. O.C.’s first bohemian beatnik coffee house, Café Frankenstein, opened in Laguna Beach in 1958. A café employee, Sid Soffer, started his own place, Sid’s Blue Beet, and in 1959 moved it from Laguna to the peninsula. Everyone from Mississippi bluesman Son House to jazzman Art Pepper (who was busted for heroin outside the club) to future Monkee Peter Tork played at Sid’s.

Soffer had his own particular way about things, like tossing customers out if they asked for salt for his beef stroganoff. He was also frequently at war with city officials, who claimed he was bringing an undesirable element into town, by which they seemed to mean the black blues and jazz musicians he featured.

Old Newport might be described as genteelly racist. They didn’t mind if you were black; they just wanted you to be black somewhere else. It was the unwritten Newport police policy back then to give persons of color a free ride to the city limits.

Not long after Sid’s opened, it was joined by another folk hangout, the Prison of Socrates, where the likes of Tim Morgon, Steve Gillette and Steve Martin got their start. A far bigger noise was right around the corner. In the late 1950s, country music aspirant Dick Dale got a job playing in a peninsula ice cream parlor. Dale caught the surfing bug, and soon found a way to replicate the sensation of shooting the curl on his guitar.

When he started playing the Rendezvous in 1961, the old dame began drawing the sort of crowds it had in the big band days, except they were doing the surfer stomp while Dale’s Fender Strat, Showman amplifier and reverb unit created more racket than any big band ever could.

He and other surf and rock bands became the staple diet at the Rendezvous, kicking Bal Week into a whole new gear. An LA Times article on Bal Week unearthed a tongue-in-cheek but apt 1960s classified ad: “Easter Week: 3-bedroom party house with view, patio and fireplace. Only two house rules: no opium smoking in elevators and guests must bury their own dead.”

Along with the music getting amped up, the crowds got rowdier. In 1965 police made a record 1,000 arrests during the week. There’s a hard-to-find photo book of Bal Week 1966—shot and written by Newport Beach cop Jerry Nikas—that chiefly shows kids having a lighthearted good time, but that was also the year the police really began clamping down, working 12-hour shifts and making 347 arrests in just the first three days.

The trend from that point on was for the city to keep kids from cutting loose, or from even getting onto the peninsula during Bal Week. 1966 was also the year the Rendezvous burned to the ground. It had done so once before, in the 1930s, but this time locals were opposed to it being rebuilt. Coincidentally, the last group to play at the ballroom was called the Cindermen.

Hippiedom never got much of a foothold in Newport. There was the Groove Company “underground” record store on the peninsula, and the neighboring Bird Without a Cage bookstore and Marxist reading room, neither of which were exactly welcomed into the Chamber of Commerce. The short-lived Bacchus nightclub on Mariner’s Mile featured heavy rock bands, and an East L.A. R&B outfit whose singer was a young Edward James Olmos.

J.J. Mack, the mainstay at the Lucky Lion, was more typical Newport fare, singing Johnny Rivers-style rock that allowed patrons to feel mildly hip while they drank their highballs. In the coked-out 1970s a new scene developed near John Wayne Airport, which became known as the Devil’s Triangle for the way partiers would lose themselves in the three main nightspots there: Blackbeard’s, Harry’s New York Bar & Grill and El Torito.

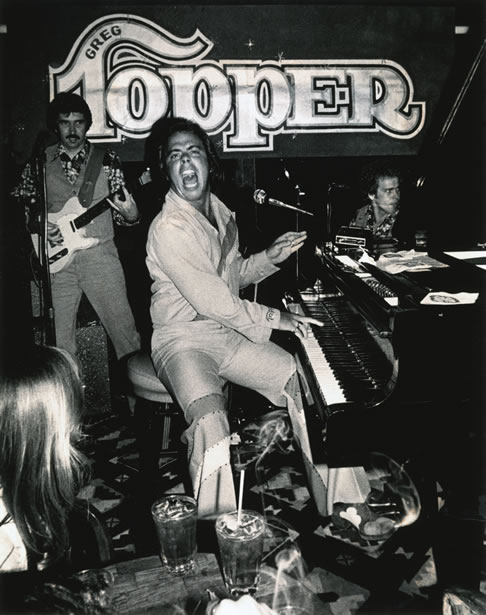

By the early ‘80s the coastal venues were reinvigorated by the hard-driving country of the Phantom Herd (featuring the late Chris Gaffney), piano-pumping rocker Greg Topper and three remarkable blues blasters: the James Harman Band, the Mighty Flyers and the Hollywood Fats Band. After these acts closed the clubs at 2 a.m., the parties would often move on to bayfront homes or yachts, and lots of people were arriving home after their newspapers did.

Bal Week struggled on, and in 1987 there was even a melee near the Fun Zone involving a crowd of 700, after a woman in a convertible flashed her personal fun zone at the street revelers. (This is apparently such an ingrained behavior—Huntington Beach’s 1986 Labor Day riot was sparked by a similar display of flesh—that it’s a wonder babies don’t riot at the sight of nipples.)

Will the town that once jumped to the sounds of Benny Goodman, and jumped higher to Dick Dale’s surf beat, and jumped through windows to the James Harman Band, ever regain its youthful bounce? Or will those halcyon days only become a fond memory shared around the fondue pot? ,